The Heritage Foundation’s Meese Center released Arresting Your Property, a comprehensive report on civil asset forfeiture—the much maligned law enforcement tool that enables law enforcement officers to seize cash and property on the suspicion that it has been used to facilitate, or is the result of, criminal activity.

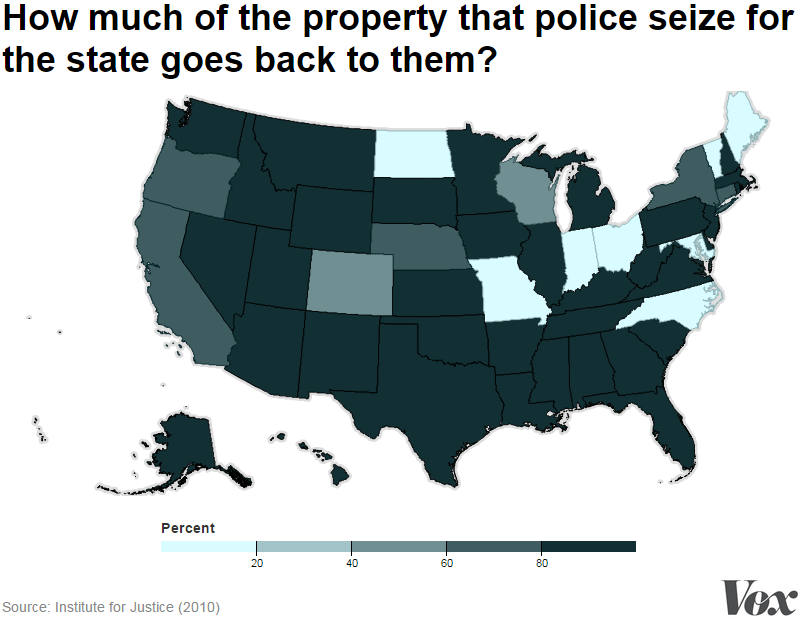

Civil asset forfeiture allows law enforcement agencies to keep the proceeds of their seizures, incentivizing police and prosecutors to zealously target money and property, often in lieu of going after the criminals themselves. And all too often, forfeiture’s targets are not criminals at all—they are ordinary people with valuable assets who happen to be carrying cash in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Meese Center has updated its database of abusive forfeitures—sixty accounts of motorists, entrepreneurs, and homeowners who have had their assets seized despite little to no evidence to corroborate claims of criminal activity. Many eventually won the return of their property, often at great personal and financial cost.

Others, sadly, had to walk away penniless because of arbitrary filing deadlines or their own inability to afford a lawyer.

And Obama’s criminal justice reforms don’t include civil asset forfeiture.

Here are four of the newest additions:

1. Nevada law enforcement agents were so eager to search Straughn Gorman’smotor home for cash that they pulled it over not once, but twice. The second stop was necessitated by Gorman’s unwillingness to consent to a voluntary search when his motor home was first pulled over along I-80.

The officer conducting the stop strongly suspected that Gorman’s vehicle contained large amounts of currency but did not have a drug dog on hand to sniff the vehicle. So he let Gorman go—and then contacted a colleague who did have a dog, and told him to look out for Gorman.

During the second stop, the dog “alerted” to narcotics, and the officer searched the vehicle, discovering and seizing $167,000 but finding no drugs. Gorman challenged the case, and a federal judge ruled that not only had the government failed to demonstrate a connection between the currency and the drugs, but the officers had conspired to violate Gorman’s Fourth Amendment rights. He also chastised prosecutors for disingenuously arguing at trial that the two traffic stops were unrelated.

The judge ordered Gorman’s money returned and invited him to file for attorney’s fees. The government has appealed the decision and is still fighting to keep Gorman’s money.

2. Eighty-one-year-old James Huff, a Nevada resident, was traveling west on I-40 in December, 2013, when he was pulled over for a minor traffic violation. The officer asked Mr. Huff if he had any illegal substances or large amounts of currency; Huff answered in the negative and then refused to consent to a search of his car. The officer’s drug-sniffing canine, however, “alerted” to possible narcotics, and a subsequent search revealed $8,400 in cash.

The officer seized the funds and immediately presented Mr. Huff with a “Disclaimer of Ownership” form, attempting to convince the octogenarian to sign away all legal interest in his money right there on the side of the road. Huff refused, intending to challenge the seizure. Six months later, the Apache County Attorney’s Office published a generic notice in a local paper that the office intended to forfeit “$8,400 in currency.”

The notice gave no specifics, so Huff and his lawyers did not know that the notice was for his money. As a consequence, he missed the deadline to file a claim, and a judge ruled that he had lost the opportunity to challenge the seizure. The money was ordered forfeited by default. Prosecutors never had to demonstrate any connection whatsoever between Huff’s money and drugs.

3. Philadelphia police raided a boarding house in 2011, seizing funds from a known drug dealer who lived on the second floor. But in the midst of the raid, police also entered the apartments of Hank Mosley and Tanya Andrews—neighbors who in no way were affiliated with the alleged illegal activity. Cops nonetheless seized $2,000 from Mosley’s apartment and $1,500 from Tanya Andrews. Weeks later, the drug-dealing boarder received a letter notifying him of the city’s intent to forfeit his money, and the ledger of assets “in his possession” included Mosley’s and Andrews’ funds. The city refused to recognize the error, and Mosley and Andrews had to hire lawyers. Eighteen months and five court appearances later, a judge denied the city’s forfeiture motion and returned Andrews’ money to her. Mosley, however, had moved to Colorado and could not make his court date. The city forfeited his $2,000 by default, despite Mosley never having done anything wrong.

4. Kevin Johnson routinely smoked marijuana in his Philadelphia home to ease joint pain. Using marijuana was undoubtedly a crime, and when police searched his home in 2012, Johnson knew he faced possession charges for two joints found under his chair. But in the course of searching the house, police also found $2,000 Johnson’s 87-year-old wife Carla had saved from her pension. Philadelphia police seized the cash, calling it the illegal proceeds of drug dealing.

Mr. Johnson was later acquitted of the charges against him, but Philadelphia refused to return the seized funds. Because civil forfeiture cases do not require criminal charges or convictions, his acquittal meant nothing. Strangely, Philadelphia intended to forfeit only $600; $1,400 of Mrs. Johnson’s money was unaccounted for.

Since a lawyer would cost more than the value of what was seized, the Johnsons decided to let Philadelphia forfeit their money unchallenged. To this day, they have no idea what happened to the missing $1,400. (The names of the Johnsons were changed by the ACLU to protect their identity.)

READ MORE: http://www.heritage.org/forfeiturereform

http://www.heritage.org/forfeitureabuse